Thorogood’s writing is so intertwined with her visual approach that the two are completely inseparable. That approach doesn’t work with It’s Lonely at the Centre of the Earth. So, normally I structure reviews by discussing the writing and visual elements of a comic separately and on their own merits, and how they interact with one another. IT’S LONELY AT THE CENTRE OF THE EARTH is an intimate metanarrative that looks into the life of a selfish artist who must create for her own survival.” The Thorogood Method “Cartoonist ZOE THOROGOOD records six months of her own life as it falls apart in a desperate attempt to put it back together again in the only way she knows how. Running the gamut of human emotion with her narrative and reflecting upon Thorogood’s life via hyper-imaginative visuals, Center of the Earth feels like something we shouldn’t be allowed to read – but will come away thankful that we can. (Nov.From rising comics talent Zoe Thorogood ( The Impending Blindness of Billie Scott, Rain) comes her deeply personal and impossibly creative autobiographical graphic novel creation in It’s Lonely at the Centre of the Earth. This has the force of a fist punching through the page.

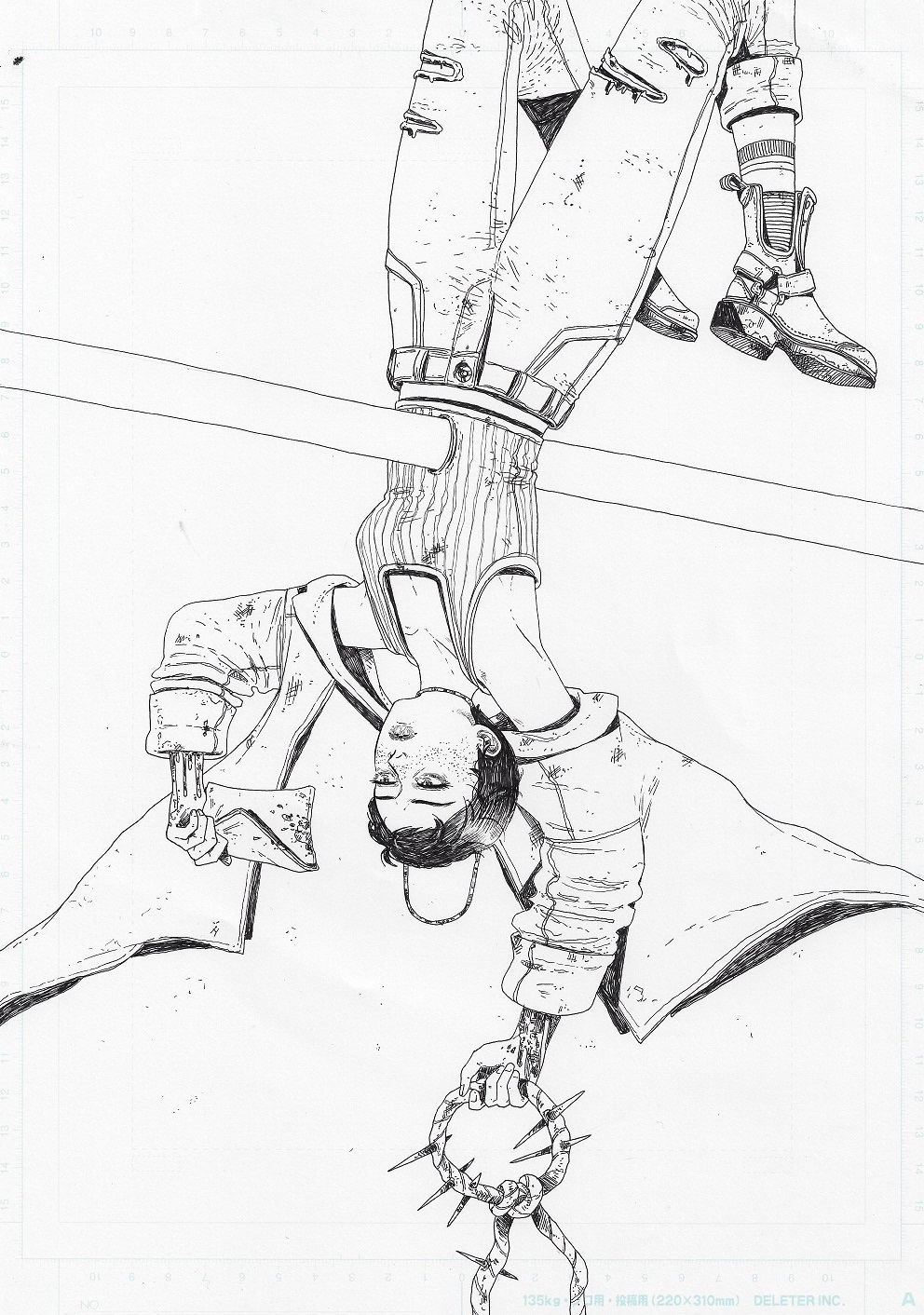

Do you have any idea how big of a base that covers?” Already pushing herself to new limits, Thorogood more than delivers on the promise of her debut. At one point, Thorogood is shocked to discover how many people find her work relatable, but reminds herself, “You’re sad and mildly insufferable. She darts manically but still dazzles the reader with constantly shifting but always stunning artwork. Thorogood is an astonishingly flexible artist, and she visualizes her obsessive self-analysis by drawing herself in diverse art styles, appearing sometimes realistically, sometimes as a big-eyed cartoon, other times with the blank face of an online meme. Battling isolation and suicidal thoughts through the Covid-19 pandemic, she focuses on concrete goals: attending a comic book convention in London, meeting an online crush in the U.S. Following the release of her well-received debut graphic novel, The Impending Blindness of Billie Scott, Thorogood finds that artistic success is no cure for lifelong depression, which she draws as a looming Babadook-like monster. “I’m in a codependent relationship with my own work,” Thorogood worries in her raw and relentlessly imaginative graphic memoir, which bristles with self-awareness of the ample pitfalls of its genre.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)